Virtual reality proponents see 5G as part of the answer to an vexing problem: What happens if you want high-resolution VR, but don’t have a powerful enough PC to run it?

Meet cloud VR, the next stage in VR’s evolution. Rendering the scene on a remote server and then streaming it to a headset eliminates the need for a powerful CPU. But fail to deliver a responsive experience, and users get disoriented and nauseous. A series of demos hosted by AT&T and Ericsson on Monday suggested a number of solutions, all using 5G as a high-speed, low-latency backhaul that proponents think could make cloud VR a future reality.

Eventually, the AR/VR industry even hopes you’ll take the technology outside, perhaps fulfilling the promise that Google Glass once offered. But to do so, you’ll need a high-bandwidth, low-latency wireless infrastructure. Here again, the 5G industry is volunteering.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGHTC’s new Focus Plus standalone VR headset. This model was modified to bypass the bullt-in Qualcomm Snapdragon processor and stream from a remote server instead.

Cloud VR isn’t guaranteed

Though there was a palpable sense of optimism in AT&T’s 5G demo room, combining the struggling VR market with the emerging 5G technology is no certainty. Next-generation 5G technology is slowly rolling out, combining both longer-range sub-6GHz wireless and short-range, high-speed millimeter-wave technology under one umbrella.

VR sales are growing, though slowly. Sony Interactive President Shohei Yushida tweeted this week that Sony has sold 4.2 million PlayStation VR units since its launch in 2016. Sales exceeded 1 million units per quarter for the first time in late 2017, according to Canalys. That number trails quarterly PC sales significantly, however, indicating that VR headsets are far from becoming a required PC accessory in the same way a mouse and keyboard are. Even Palmer Luckey, the inventor of the Oculus Rift, wrote in 2018 that “no existing or imminent VR hardware is good enough to go truly mainstream, even at a price of $0.00.”

Luckey’s conclusion was that VR required an overall better experience—and that’s what the companies demonstrating their visions of the future said that they can achieve, on several fronts.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGThe AT&T / Ericsson Internet lab built out for the demonstration.

The first challenge: Minimizing latency

The highest-profile technical obstacle to good VR is still latency. Remember that 90 frames per second is considered the benchmark for stable virtual reality—any less than that, and the latency in rendering the image imposes a feeling of disorientation and nausea. Though much as been made of 5G’s bandwidth, it was the low latency that the companies at the AT&T showcase kept coming back to as the real selling point for 5G.

With cloud VR, the key metric is the overall latency in milliseconds between the headset and the back-end server. If you jerk your head around, the system has to render the scene as soon as possible, or you’ll get nauseous.

According to Wen-Ping Ying, HTC’s executive director of technology planning, the magic number for rendering “motion to photon” nausea-free virtual reality is about 20 milliseconds, which 5G more than satisfies, with latencies of between 5 to 8 ms. (Several executives told me that designing for fixed Wi-Fi was actually easier, but that the mobility problems roaming around a 5G network were the challenge they wanted to solve to make 5G a reality. Network latencies are also going to vary depending on a number of conditions.)

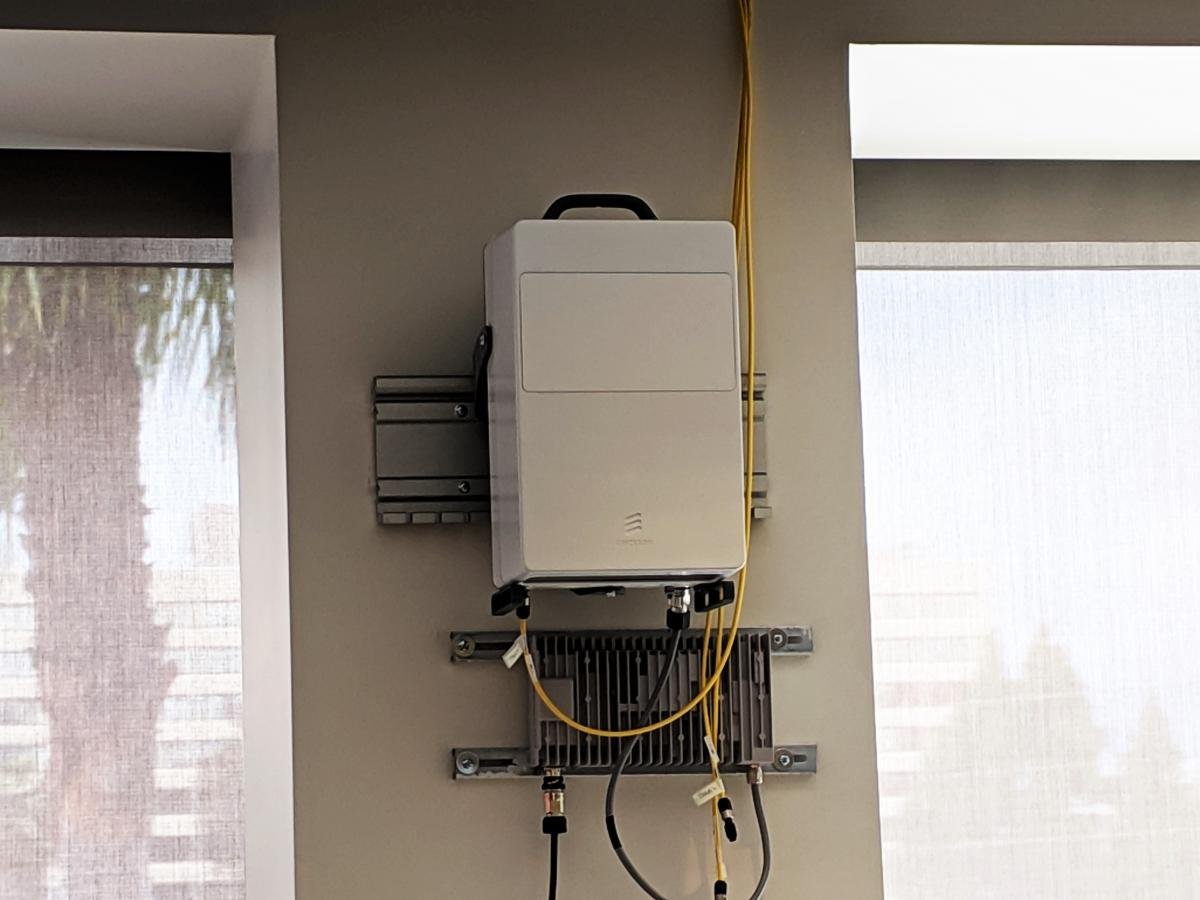

To show that those kind of low latencies were possible, AT&T’s Foundry program helped build out a small 5G demonstration facility inside Ericsson’s Silicon Valley headquarters. It consisted of a server room with network gear, along with a 5G small cell that served as an access point for the entire room.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGEricsson’s equipment was used as the local wireless infrastructure.

Essentially, all of the demos were what you would get if you combined VR and cloud gaming—quite literally, in fact, at Nvidia’s booth. There, I played Beat Saber, a rhythm game where timing is everything, streamed over 5G from a “remote” Nvidia RTX server installed a few dozen feet away. Though I noticed some interference from competing HTC Vive “lighthouses,” the game itself streamed just fine, with no noticeable slowdowns. The remote-rendering VR technology could end up as part of Nvidia’s GeForce Now, executives said—an intriguing possibility that probably won’t happen until 5G becomes mainstream.

Likewise, HTC demonstrated its vision of VR on the new HTC Focus Plus, a $799 standalone headset with new six-degree-of-freedom (6DoF) controllers. PlayGiga also showed streaming an underwater exploration game, SubNautica, over 5G to a VR headset.

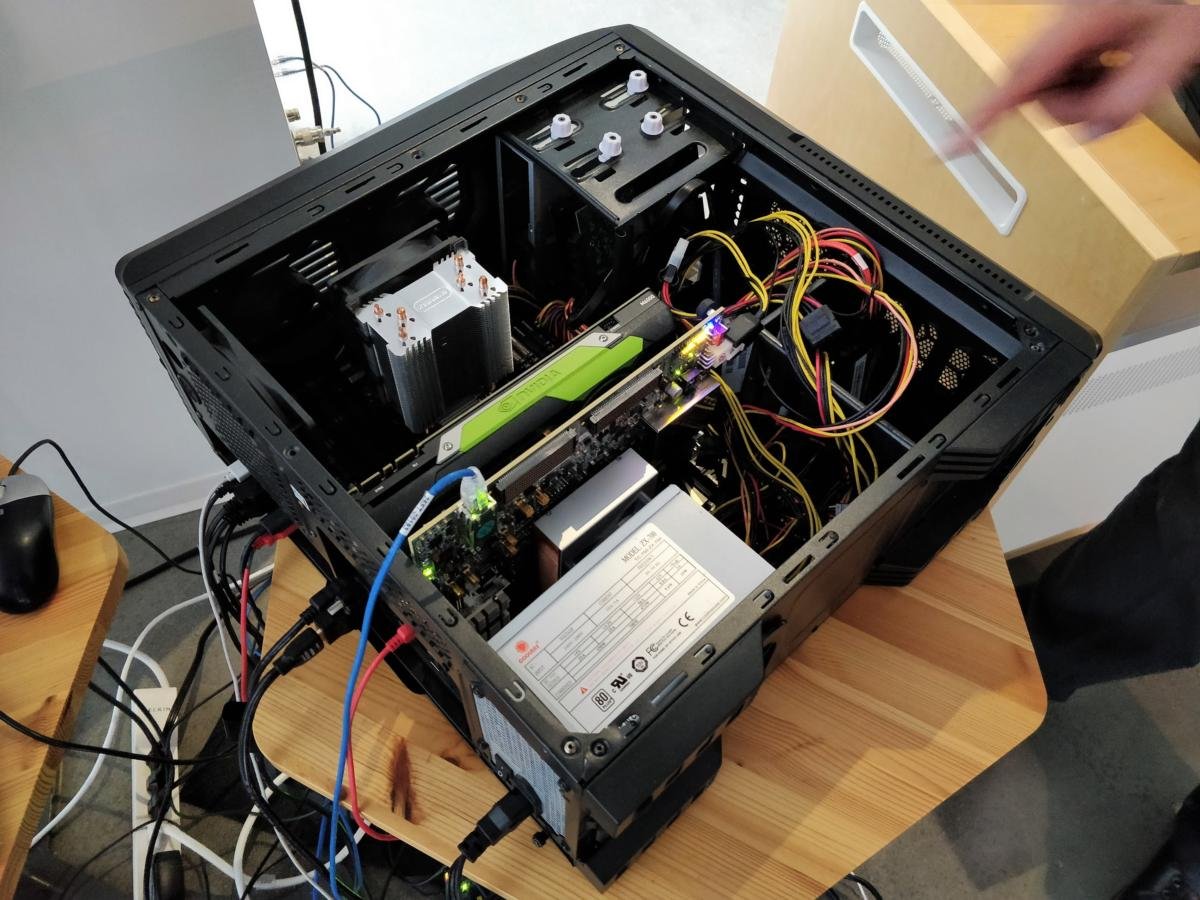

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGNGCodec uses an FPGA board to help offload some of the CPU workload used for streaming.

Though the Focus Plus is powered by a Qualcomm Snapdragon 835, HTC modified it to render the scene remotely, and then send it to the headset using the room’s 5G network. HTC used a timing-based game (PopStic VR, a Beat Saber clone), and the timing worked well. There were a few stutters tied to how the headset detected the controllers.

The second challenge: Upping the resolution

Though the demonstrations by HTC and Nvidia tried to show how 5G could minimize cloud VR’s latency, several others tried to show off how 5G could compete with traditional high-resolution VR, too.

GridRaster, like HTC, used a custom streaming application to stream a 15-million polygon model of a jet engine to a first-generation Microsoft HoloLens, co-founder Dijam Panigrahi said. Microsoft’s latest HoloLens, the HoloLens 2, can render only 100,000 polygons. But Microsoft’s working hard to catch up: An Azure-powered technology called Remote Rendering will eventually stream 100 million polygons, the company has said. To ease the rendering compute load, NGCodec showed off an FPGA board that compressed the streamed VR data in real time.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGTraditional cloud gaming, from CloudGiga, was on display as well. The company showed Subnautica streamed wirelessly to a VR headset as well as Rise of the Tomb Raider, streamed to a phone.

Can ‘edge devices’ combine the two?

One question that hasn’t been resolved is how you reconcile the two: low-latency VR, combined with the resolution of a tethered device. While we’ve become used to the client-server model—your PC asks a cloud server for a file, and it’s delivered—cloud VR may depend on what’s called a third piece of hardware, a so-called “edge device,” connected by 5G, at least to the cloud. In this scenario, the headset requires very little processing power, except to decode the streamed VR data. The edge device and the cloud share the bulk of the storage and rendering power.

The term “edge device” is confusing, not the least because it’s relatively undefined. It could be a dedicated box that sits near the user, or a small caching server that a carrier like AT&T could place next to the cell tower. It most likely could be a PC, with a discrete GPU (or not). HTC sees its recent HTC 5G Hub as a potential cloud VR gateway, Ying said, but also a potential edge device—the hub includes its own built-in Snapdragon 855 chip.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGGridRaster used a remote server to stream a high-resolution AR hologram to a first-generation Microsoft HoloLens.

“Now your VR device can be a very dumb device, receiving the streamed VR data from this endpoint,” HTC’s Ying said in an interview. “We leverage this as a gateway for sending the uncompressed image—this can be dirt-cheap. As a replacement for the PC, this is the best we can think of right now.”

“In the future you’ll see more flexible, scalable rendering,” Ying added.

All this assumes, of course, many many things: that 5G will roll out in a timely fashion; that it will be priced affordably; that data caps either won’t exist or won’t impede cloud VR adoption. Technically, the experience must match the carefully tuned experience of the demo room. It also assumes that software developers will be able to either port or develop the same compelling content that dominate the PC and console space—and that’s assuming cloud VR doesn’t solely exist as a business tool. Finally, all this will have to convert the customers who haven’t bought into the first generations of VR gear.

For all that, what we saw of cloud VR is that it works. But whether it evolves into a product you’ll buy is another thing entirely.

![A woman wearing a virtual reality [VR] headset.](https://techproarena.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Combining-VR-with-5G-to-create-cloud-VR-assumes-a.jpg)