Anyone who’s experimented with a cloud gaming service knows that wired ethernet is almost required. Wi-Fi? Games can lag somewhat. And over cellular? If it’s a fast-paced game, you’re just asking for trouble. But cloud gaming over AT&T’s prototype 5G network was actually…impressive?

At AT&T’s Spark conference in San Francisco on Monday, I had a chance to try out Nvidia’s GeForce Now service for PCs running over AT&T’s 5G service, playing the newly-released Shadow of the Tomb Raider game on a generic Lenovo ThinkPad.

The traditional way to run a PC game is locally, running the game off a hard drive or SSD on your PC, using the CPU and GPU to render the game as fast as it can. The downside, of course, is that you have to buy all of that hardware yourself.

Cloud gaming renders each frame of the game like a Netflix video, streaming it down to your PC. The trade-off is that the 3D rendering takes place on a remote server—a cheaper solution than buying a high-end graphics card, at least in the short term. But every wiggle of the mouse or press of a button must be sent up to that server, processed, and the results sent back to your screen.

All that back-and-forth adds latency, the delay that makes the difference between a responsive action game and one that you give up on because of noticeable lag. (Latency typically depended upon how far your PC was away from the server.) According to an Nvidia representative, early implementations of cloud gaming services like OnLive suffered from delays of 100 milliseconds or more.

Mark Hachman / IDG

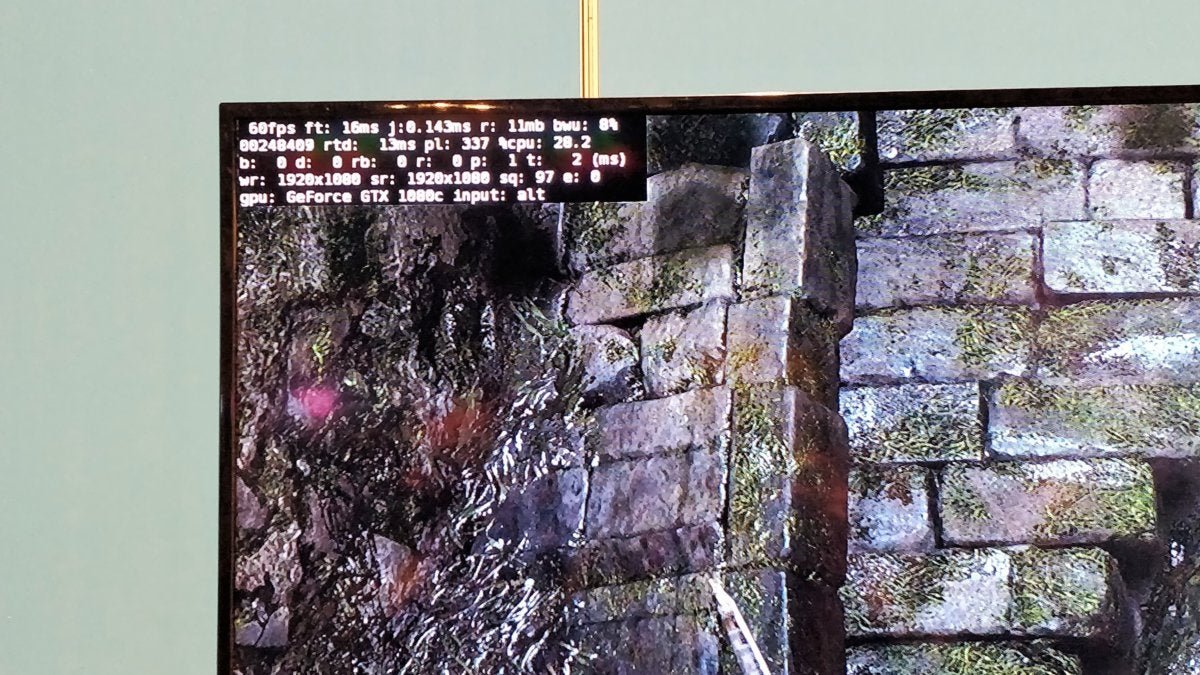

Mark Hachman / IDGThe overlay supplies a lot of data about what’s going on here: the bandwidth that’s being sent over the connection (which isn’t much, given that this is a static scene); the round-trip (rtd) latency; the resolution; and the GTX 1080 being used to render the scene in the server.

At the AT&T Spark event, an overlay atop the Tomb Raider screen showed that latencies rarely climbed above 15 ms or so, which resulted in surprisingly smooth gameplay.

Typically, requesting a webpage via your phone sends the request wirelessly to the local cell tower, which then routes it over the standard wired network. What Nvidia and AT&T showed off worked a bit differently. Instead of a 5G dongle attached to the PC, the signal was sent via Wi-Fi to the local access point, then down to Nvidia’s closest GeForce Now server in Santa Clara, Calif. The signal was then sent from the server through a Cat5 cable to AT&T’s 5G router, across the 5G link, and then from there back to the Internet (and back to the client PC.)

Granted, we didn’t have a chance to do too much more than run around a deserted tomb, shooting a few of our heroine’s arrows at rats and a skull or two. The true test of a cloud-gaming scenario is how it feels when you need to react quickly to what you see onscreen. But the overlay also revealed the bandwidth sent over the server, which was very low when the scene remained fixed or was rotated slowly. But when we whipped the mouse around, back and forth, the overlay revealed that we were sending 30 Mbps back and forth. (The game was rendered in 1080p, using High settings.) Again, there wasn’t any noticeable lag.

One of the interesting omissions at AT&T’s Spark event was any disclosure of the availability bandwidth that 5G will bring, even though the company touted its progress in millimeter wave technology and what cities would receive AT&T 5G coverage in 2018 and 2019. (Look for more 5G announcements later this week, as the Mobile World Congress show kicks off in Los Angeles.) Instead, the message was all about low cellular latency, and what advantages that would bring.

What this means for you: It’s difficult to believe that consumers will end up playing cloud-rendered versions of Fortnite on a small laptop like the Surface Go on their way to work, even if everything works as advertised—and demonstrations are supposed to work as advertised. Real life, especially where cellular connections are concerned, often doesn’t. Nevertheless, what we saw held out hope that AT&T (and presumably other carriers) aren’t just concerned about bandwidth, but about a quick, responsive network connection. Yhat’s something that we can get behind.