“You may or may not find it appealing, but the Plaud Note is the most practical kind of AI hardware — and it exceeds expectations.”

- Stunningly thin and light

- Fairly accurate transcriptions

- Summarization templates are neat

- Choice between AI models

- Much better than similar phone apps

- All features locked behind a subscription

- Non-English transcriptions need polish

At Digital Trends, we recently analyzed an orange piece of AI hardware. It didn’t fare well. “The worst gadget I’ve ever reviewed.” That was the summation for the Rabbit R1. The Humane AI Pin also didn’t hold up well in the hands of experts, and the company is currently reeling from a situation where it’s getting more returns than it can sell fresh units.

- What it’s like using the Plaud Note

- Some extras, some pitfalls

- But, but, but… there’s an app

- Phones have AI, too

- Should you buy the Plaud Note?

Since that first wave ebbed, we have seen another round of AI gadgets popping up on the scene, promising fancy AI companions that are always listening and learning from your day-to-day interactions. But if AI companions — especially those seeking deep emotional connection — have taught me anything, they are pliable and not in the right way.

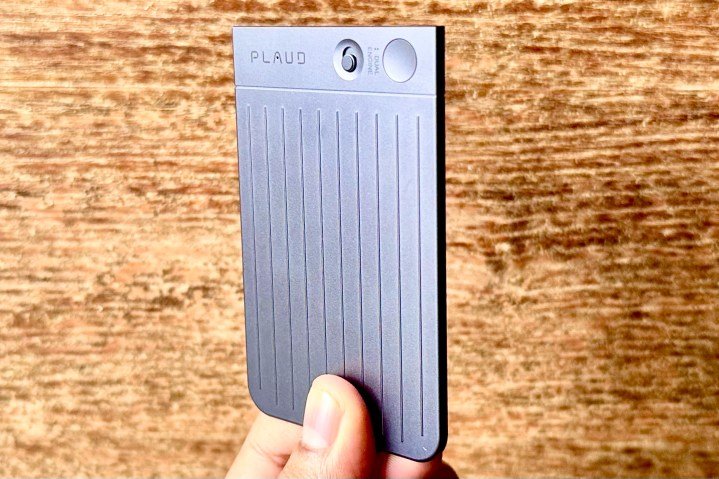

San Francisco-based Plaud has a rather modest approach to AI hardware, one that banks more on practicality than claims to putting human ingenuity to shame. Its first offering is Plaud Note, a sleek snap-on device that deploys generative AI for something as simple as recording voice notes. It transcribes them, too, with an added dash of summarization convenience thrown into the mix. But is it any good?

What it’s like using the Plaud Note

The Plaud Note is almost as thin as the buttons on the iPhone 15 Pro. It’s ridiculously light, but at the same time feels fantastic to the touch. And the best part is that there’s nothing in terms of a learning curve. The setup is a walk in the park, and all you need to do is press the round button until you feel the vibration motion inside and see the red blinking light.

See that tiny physical toggle? When it’s down, the Note’s mics collect sound signals from your environment. Flick it up in call mode, and a vibration conduction motor kicks into action and records your calls. Connection with your phone is established via Bluetooth, and the moment you open the app, all the recordings appear neatly arranged as a list, with the latest one sitting at the top.

If you are an English speaker, or your work relies on communication in the English language, the Plaud Note is a reliable choice. I tried it with a variety of accents, and it worked fine. The only hiccups happened with heavy Scottish, but the transcription was still usable, to my surprise.

Where it struggles is with technical terms, stylized names, or colloquial phrases. For example, it mistranscribed “GPT-4o” as “G34,” while “Claude Sonnet” appeared in the transcription as “CloudSonic.” However, that can also be blamed on the pronunciation clarity. The transcription often picked up my brother’s voice clearly and transcribed it accurately, but made occasional errors with my voice, even though I was reading the exact same passage.

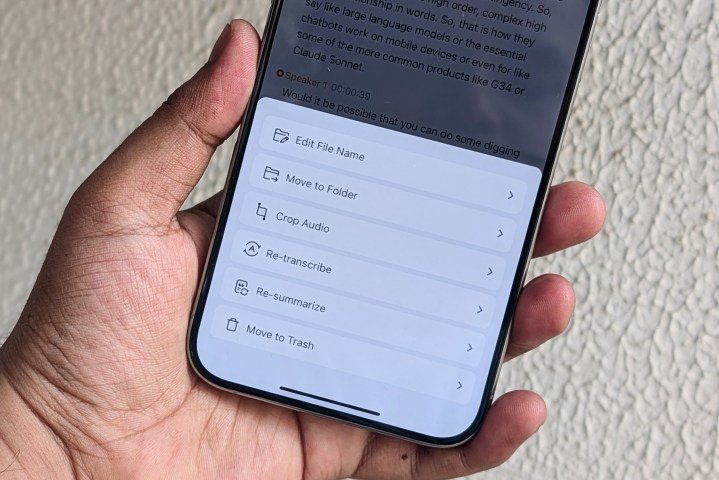

For these errors, you can edit the transcription before you share or export it locally. But there’s a minor annoyance here. An edit made in the transcription text file doesn’t automatically reflect in the summary or the mind map. Thankfully, the app offers dedicated options for a second attempt at transcription as well as summarization.

The Plaud Note is a reliable choice.

Aside from English, I tried transcriptions in Hindi, Urdu, Persian, and Arabic. Even with classical Urdu literary commentary — which is essentially the same contrast to the regular Urdu language as Victorian English to its modern 21st-century version — the Plaud Note did an impressive job.

The transcribed text did a decent job and to a level of accuracy that I wasn’t expecting from a non-English language. And based on the transcription at hand, it also did an admirable job with the summarization.

But the spelling struggles are evident from the get-go, and if I were to quantify them, the accuracy would be somewhere around 85%-90%. These errors can squarely be blamed on the underlying language model, which has been trained predominantly on English and orders of magnitude lower for Urdu data.

Another reason for these mistakes is how these languages are written. Take, for example, Urdu, Arabic, and Persian. All three follow the same fundamental scripting rules. Unlike English words — where a collection of letters forms a word, yet each letter is still distinctly visible in its original uppercase or lower form — those rules don’t apply to aforementioned languages.

In these scripts, words are composites where letters change shape depending on the length and possibilities of keeping them discernible. Moreover, the system of “aeraab” makes the letters representing “O,” “E,” and “A” invisible, while the system of “izaafat” that joins two words with an “e” further complicates things.

All these nuances mean the transcription you get often produces words that read about right, but are actually inaccurate from a scripting perspective. I handed the Plaud Note to a Portuguese teacher at a local embassy, and following a brief test run, they surmised that the device can understand native accents just fine, but will struggle with non-native speakers.

The ball is not in the hands of Plaud here. The onus falls on the makers of underlying AI models to diversify their training data to cover more languages and accents. Talking about AI models, you get a choice between GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 for transcription and summarization. When compared, OpenAI’s GPT-4o proves to be the more reliable option with a healthy margin.

Some extras, some pitfalls

There’s some difference between the raw quality you get from voice recorded from an ambient source — like a human or a speaker — and voice calls. The former turns out fine, but phone call recordings sound a bit subdued, which is not entirely unexpected. This also affects the quality of transcriptions you get from the AI.

To improve the situation, the Plaud app offers a voice gain system that lets you adjust the sensitivity of the onboard mic so that it can pick up voice from the phone’s earpiece more accurately. But depending on the level of ambient noise, increasing the sensitivity too much also lets more noise creep into the recordings.

It takes a bit of experimentation to get it right for voice calls and extract the best-quality audio recording. However, what you get also depends on the network quality and whether the call is made over a cellular line. Wi-Fi and WhatsApp calls were fine, but indoors, the Plaud Note occasionally struggled due to network interference.

As far as the transcription quality goes, it’s pretty darn close to what you get from the Recorder app that comes pre-installed on Pixel phones. In my experience, this app has been the most accurate over the years, but I won’t have any qualms about replacing it with the Plaud Note, especially considering the fact that the latter offers ready-made templates for summarizing the contents into presentable formats.

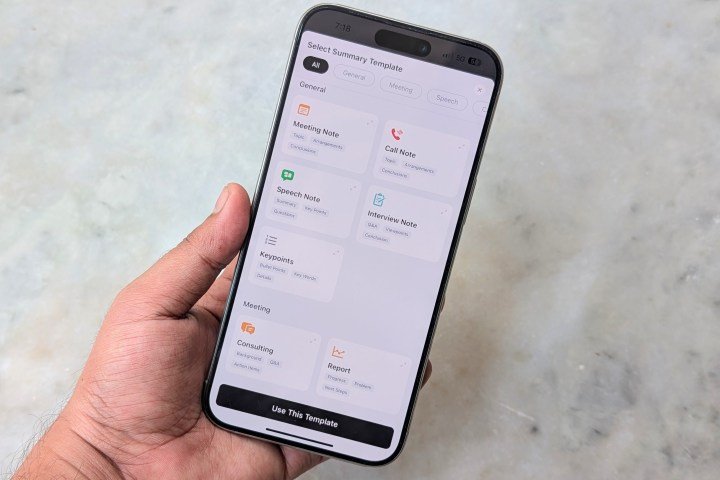

The templates work quite nicely, as well. I recorded a speaker session during a virtual seminar, and the “lecture” summarization note not only picked up an eerily good headline but also created a clean document interspersed with core bullet points and subheads. I’m not really a fan of mind maps, but that facility is available.

Thankfully, you can choose to do a fresh transcription and change the summarization template for any existing audio clip. What I love the most about the Plaud Note approach is that you can do it all in one app, instead of jumping between web services and apps to do the same.

But, but, but… there’s an app

There’s a strong case to be made here that an app can do everything Plaud Note can. In fact, now that phones are running AI engines locally, a healthy bunch of them are offering offline recording, transcription, and translation features. However, each approach has its own set of perks and drawbacks. Let’s address the app situation first.

Take Otter, one of the most popular voice recording and transcription apps out there, especially among business professionals and journalists. It relies on a subscription model that costs $8.33 per month, while the Plaud personal tier costs $6.59 for a month, even though both limit you to 1,200 minutes worth of recording.

The biggest advantage of the Otter is that it relies on the superior mics fitted inside a phone, which means the recorded audio sounds much better. But it’s nowhere as versatile as Plaud Note, and that boils down to the deployment of AI. Otter only supports the English language at the moment, with multiple accents to go with it. Plaud Note has OpenAI’s GPT-4o running the show, which offers support for 59 languages and it can handle accents just fine. The biggest advantage of deploying AI for transcriptions is that it makes corrections on the way instead of just transcribing a misspelled jargon and moving ahead.

Just try voice typing with the Google Keyboard mobile app or in Google Docs. The AI makes corrections in real time as you speak your way to a note or article. In addition to making corrections — spelling, grammar, or stylistic consistencies — it learns from what you speak ahead and makes necessary corrections in the preceding blocks of words or sentences.

That’s the fundamental concept of conversational chatbots for you. Language models are trained to predict the next word. Experts refer to this behavior as statistical contingencies, something the human brain is particularly good at. Essentially, it is the complex high-order relationship between words, which come together to form a cluster that makes sense as a coherent language.

Similar apps are nowhere as versatile as Plaud Note.

The situation with AI is only going to get better over time, both in terms of accuracy and diversity. For example, there’s Meta’s open-source No Language Left Behind (NLLB-200) model, which supports translations in over 200 languages. But AI goes beyond just spelling and grammar corrections in transcribed audio clips on the Plaud Note. It is going to summarize your voice notes, create mind maps, and even come with a bunch of templates that neatly filter and condense contents into an easy-to-grasp format.

Another rather practical advantage is the storage situation. As a journalist, I often can’t bring myself to delete voice recordings of an interview, even after fact-checking and publishing the relevant story. “You never know what nugget of information you might find in an interview log,” I often tell myself. That eats up into the phone’s storage.

The worst part is that modern phones don’t allow storage expansion through microSD cards. And even if you’ve purchased a higher-end version, you will eventually have to export them. With the Plaud Note, you get 64GB of native storage, so there’s that definitive advantage, too.

Phones have AI, too

Galaxy AI. Apple Intelligence. Google AI on Pixels. All these solutions can accomplish some fantastic stuff. Occasionally, they flub, churning out stereotypical mess or showing no restraint at turning a kid-favorite cartoon character into a Nazi demon. There’s also the fact that these AI solutions won’t always be free.

But let’s assume we live in a fair world and brands suddenly feel philanthropic with AI. You would still need to pay dearly just to own the hardware that is running all that AI wizardry, because AI, especially the on-device kind, needs a lot of firepower. So much so that Apple Intelligence is only available on the iPhone 15 Pro and Pro Max.

Galaxy AI is also limited to higher-end Samsung phones. The situation likely won’t change this year. Or in the immediate year ahead. That’s because offering next-gen AI on a phone depends as much on the silicon available as it does on product decisions made by a brand. You can’t expect to get 12GB RAM (almost the baseline for local AI tasks) on a budget phone, after all.

Yes, AI will drive phone sales, according to analysts, but the silicon firepower isn’t reaching a stage where it can run fancy AI stuff on a budget phone. And without a fee attached to access it. With the Plaud Note, you can pair it with any iPhone or Android, without having to worry about the clock speed of the processor under the hood.

Instead, you just put a magnetic ring on the rear of your phone, stick on the leather case, and hit the record button. And if your needs don’t exceed 300 minutes of recording and transcription per month, you don’t even have to pay the nominal subscription fee.

Should you buy the Plaud Note?

Right now, if you’ve got a fairly recent flagship phone, you don’t need the Plaud Note, but for the rest, it’s a fulfilling solution to a practical need. iOS 18 introduced a native call recording and transcription system. And since these recordings are automatically imported to the Notes app, you can summarize or reform them using Apple Intelligence’s Writing Tools, assuming your phone supports the AI toolkit.

Google, on the other hand, is finally allowing native call recording in the U.S., starting with the Pixel 9. Google calls it Call Notes, and deploys on-device Gemini Nano AI for analysis, transcription, and translation. Just keep in mind that these features are still exclusive to only a small number of phones at the moment. Also, irrespective of the platform, these AI features might not be free forever.

In a nutshell, there’s a high cost to be paid with loyalty to a phone. For the rest, the Plaud Note is a reliable, all-in-one solution. It does a fairly good job at transcription, deploys AI to convert them into meaningful formats, and offers granular sharing as well as export controls.

It’s the entire hardware-software stack at play here and the collective convenience it offers that lifts Plaud Note above the skeptical “it could’ve been an app” argument. And for people who have been yearning for a standalone recording and transcription solution like the Plaud, such arguments won’t matter either way. Plaud Note has already crossed $10 million in sales, so there’s definitely a niche willing to pay for it.